Beijing is making its mark in Latin America.

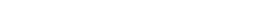

In 2000, China was the seventh-largest export market for Latin America and accounted for less than 2% of the region's exports. Today, China accounts for 10% of Latin America's exports and is the leading export destination for Brazil and Chile.

But that's not the whole picture. The United States and Europe remain Latin America's most important trading partners (as shown in the barchart below). And, China's rise, albeit significant, should be put in the context of a broader shift towards a world in which emerging markets have greater economic weight.

Moreover, the US remains a key provider of remittances to Latin America — accounting for 75% of the USD 60 billion the region received in 2008 — and so is a critical source of foreign exchange for many countries in the region.

Closer examination also reveals that there is a marked difference between China's importance as an export market for the Latin America region as a whole – predominantly focused on natural resources – and as an export market for Mexico, whose export products often compete with China's output.

But, overall, there is no question that investment into Latin America from China is increasing at a record pace. China is now the third-largest external investor in the region, behind the US and the Netherlands.

According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America, China’s foreign direct investment in Latin America reached USD 15.3 billion in 2010 and USD 22.7 billion in 2011, up from much lower levels in each of the previous nine years.

Global market implications

So what are the global market implications of China's emergence in Latin America? Significant as it is for the region’s economic prospects, China’s emergence is only one aspect of the way in which emerging economies are rapidly reshaping the global economy.

Already, in purchasing power parity terms, four of the seven largest global economies — Brazil, Russia, India and China — are 'developing' countries. According to projections by the US' Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (in its Juggernaut report on how emerging economies are reshaping globalisation), Mexico will join the world’s top seven economies by 2030 and Indonesia by 2050.

By then, the US will be the only currently advanced country to rank among the world's seven largest economies.

At the same time, China will become the centre of world trade, representing by far the largest trading partner for most countries. Its share of world trade will reach 24% by 2050, up from about 10% today.

Opportunities for Latin America

The rise of emerging economies, including China, will create major opportunities for Latin American countries. Today, about 40 per cent of Latin America’s exports go to developing countries, including China; this figure will surge as developing countries’ share of world exports more than double from 30% in 2006 to 69% in 2050.

Moreover, the rise of Brazil and Mexico, and their burgeoning middle classes, will be a boon for other Latin American economies. Brazil already accounts for a quarter of intraregional exports.

The emergence of the developing world and weaknesses in advanced economies — income inequality and political gridlock in the US, the debt crisis in the Eurozone, and the fiscal and demographic crisis in Japan — will lead to a very different economic order, one in which huge new markets and new sources of competition will arise, and one in which power and influence are more widely distributed.

For the first time, the world’s largest and most powerful economies will be relatively poorer nations.

Challenges for Latin America

Economists from Carnegie's International Economics Program argue that China's rise, and the broader shift of the world's economic centre of gravity, raise at least three economic policy issues for Latin America to address: what they call 'comparative advantage; priorities for economic diplomacy; and the region’s role in the global order.

Contrary to popular impression, the economists assert that Latin America’s commodity exporters cannot be sure that the rise of China, and other developing countries, will sustain a commodity price boom in the longer term, so diversification of their economies remains a challenge.

For nearly all commodities (petroleum could be a partial exception), increased demand may well be eventually matched by increased investments in supply and technological innovation that reduces production costs and develops new substitutes — as has happened historically.

As business conditions in Russia, Indonesia, Africa and other natural resource exporters improve, so too will their capacity to export commodities.

Moreover, demand for commodities in Latin America will eventually be held back by a natural shift to services and goods as incomes rise, as well as by innovations which reduce the wastage and intensity of commodity use.

Latin American resource-based economies may sooner or later need to strengthen their capacity to produce goods and services, the demand for which will soar as the middle class burgeons domestically and in other emerging markets.

At present, nearly 90% of Latin America's exports to China are in mining and agriculture. Although the region's terms of trade have improved, on average, by nearly 4% annually between 2002 and 2008, compared to 0.5% a year between 1995 and 2001, there is no guarantee that this recent favourable trend will persist.

Given structural changes in global demand and supply implied by the rise of the emerging powers, and uncertainties inherent in predicting commodity prices, Latin America's development strategy should, say the economists, encompass a number of economic strategies — such as investing in education, strengthening governance, improving the business climate, and enhancing the capacity to innovate.

Economic diplomacy

Although the relative size of the US economy is expected to decline over coming decades, the US is projected to remain an important destination for Latin America's exports, even in 2050. Similarly, although the importance of individual European economies to Latin America will decline over time, the European Union as a trading bloc is likely to remain among the region’s major trading partners.

So, while Latin American countries will need to reorient their economic diplomacy towards emerging powers — including fostering trade and investment agreements — relationships with Europe and the US will remain critical.

Global responsibility

Latin American countries are becoming more influential on the world stage. Brazil and Mexico are already playing a prominent role in the G20, the new premier forum for global economic decision-making, of which Argentina is also a member. But as their economic power continues to grow, say the economists, they will need to assume greater responsibility in shaping and contributing to international economic integrity.

Latin America's countries need to define their own vision of how the global trading system, financial regulation, migration policies, development assistance, and efforts to mitigate climate change should evolve.

With power comes responsibility.

UHY has offices in China and in Latin America, including in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru. For details:

Contact: Dominique Maeremans

Email: d.maeremans@uhy.com